What is Alda?

Alda’s ambition is to be a powerful and flexible music programming language that can be used to create music in a variety of genres by typing some code into a text editor and running a program that compiles the code and turns it into sound. I’ve put a lot of thought into making the syntax as intuitive and beginner-friendly as possible. In fact, one of the goals of Alda is to be simple for someone with little-to-no programming experience to pick up and start using. Alda’s tagline, a music programming language for musicians, conveys its goal of being useful to non-programmers.

But while its syntax aims to be as simple as possible, Alda will also be extensive in scope, offering composers a canvas with creative possibilities as close to unlimited as it can muster. I’m about to ramble a little about the inspiring creative potential that audio programming languages can bring to the table; it is my hope that Alda will embody much of this potential.

At the time of writing, Alda can be used to create MIDI scores, using any instrument available in the General MIDI sound set. In the near future, Alda’s scope will be expanded to include sounds synthesized from basic waveforms, samples loaded from sound files, and perhaps other forms of synthesis. I’m envisioning a world where programmers and non-programmers alike can create all sorts of music, from classical to chiptune to experimental soundscapes, using only a text editor and the Alda executable.

In this blog post, I will walk you through the steps of setting up Alda and writing some basic scores.

But first, a little history.

UNC and MML

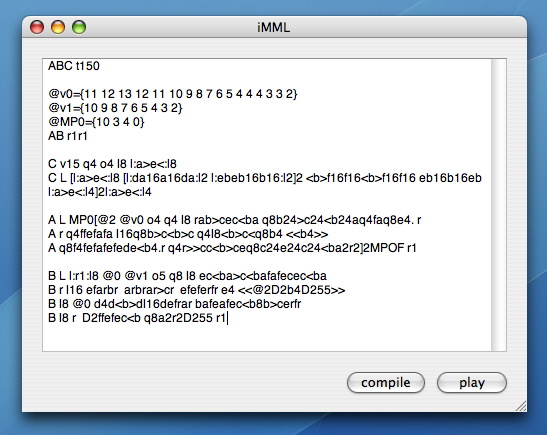

I can trace the origins of Alda back to 2004. At the time, I was studying Music Composition at UNC and exploring ways to make electronic music. I mucked around in FruityLoops a bit without much success. Eventually, I stumbled upon an entire world of music programming. My gateway drug was MML, which was (and perhaps still is) the most legit way for chiptune musicians to make NES music. After reading through Nullsleep’s excellent MML tutorial and learning how to make some rudimentary NES music, I started to become more involved in making music with human beings and took a hiatus from MML. But the seed had been planted for a lifelong obsession with the idea of programming music.

MML ended up becoming a major influence on Alda. I really enjoyed the workflow of creating NES music by writing code in a text editor. But what I wanted was a more general-purpose music programming language. I wanted to take MML’s approach to generating NES music and extend it to other realms of digital music creation: additive/subtractive synthesis, electroacoustic music, and even classical music.

Classical music?

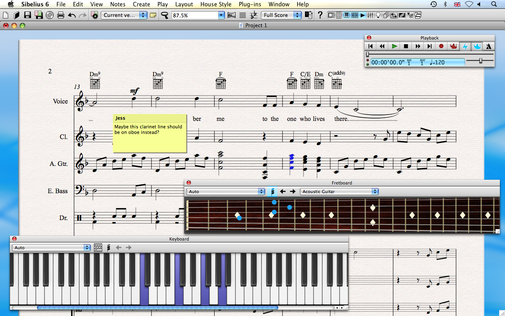

I was a classically trained musician long before I was a competent programmer. My music education led to a particular interest in composing music in a variety of styles. Growing up around computers, I discovered an ever-expanding class of GUI applications designed to help musicians compose music. I wrote guitar tablature with Guitar Pro, and for traditional music notation I have tried, at various times in my life, Cakewalk, Noteworthy Composer, Finale, Sibelius, and MuseScore, among others.

When I was studying music composition, I got a lot of mileage out of Sibelius, in particular. I used Sibelius extensively to transcribe pieces of music as I composed them. It allowed me to have a digital record of my compositions, and it was essential (practically a requirement) as a way to print out individual instrument parts to distribute to the musicians who performed my pieces.

Music notation applications like Sibelius are clearly a very important tool for people who are serious about composing music. However, as a programmer and as a composer, I feel that there are a couple of fundamental problems with GUI music notation software:

-

It’s distracting. When pre-digital age composers used to write music, they would sit at a piano and write it out by hand on staff paper. All of the notation techniques, the layout of their scores, everything, came directly from their minds and through their pens. When you notate music using a GUI application, you have menus upon menus in front of you from which to select whatever elements of music notation you wish to use in your score. This is distracting in two ways:

-

It’s not always easy to find what you’re looking for. By the time you find it, you may have lost your train of thought.

-

Having all of these music elements in front of you is visually distracting. When I used Sibelius, I would sometimes end up distracting myself for long stretches of time as I perused all of the different music notation elements it was possible to place, or browsed through all the project templates available.

In contrast to working with these complex GUI applications, I have found that programming pieces of music in a text editor is a pleasantly distraction-free experience.

-

-

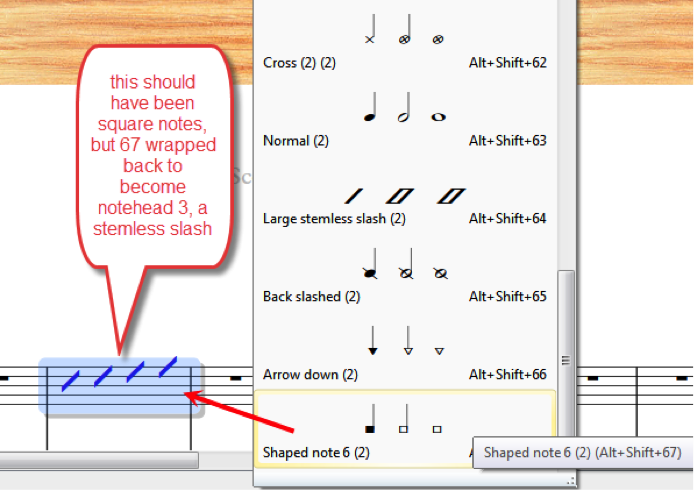

It’s limiting. I think for a composer to have an ideal environment to compose in, they need to get back to the basics. They need a blank canvas and a way to notate music. And because this is the 21st century, their scores need a way to be interpreted by a computer and turned into audio. It would also be nice if their scores could be easily converted to and from the standard notation format that human musicians are trained to read.

The GUI programs available today do an excellent job of handling these 21st century requirements, but they do so by taking a shortcut – they skip the “blank canvas” part. Of course, when you create a new score in Sibelius (for example), you do have what looks like some empty lines of staff paper, but in fact, this blank staff paper carries a very different connotation than does a physical page of manuscript paper. You can’t just grab a pencil and start writing whatever your heart desires. There are a number of hidden restraints that the GUI application forces upon you.

This is an inherent shortcoming of any GUI music notation editor; in order to be able to represent your musical score visually in a sane and comprehensible way, it has to impose some restrictions. Audio programming languages must also impose restrictions (in the same sense that any piece of software does), but because they are not tied to visually representing your score and maintaining a user-friendly GUI interface, they are able to get away with imposing substantially less restrictions on the composer. As a composer myself, I find this fascinating and inspiring.

A taste of Alda

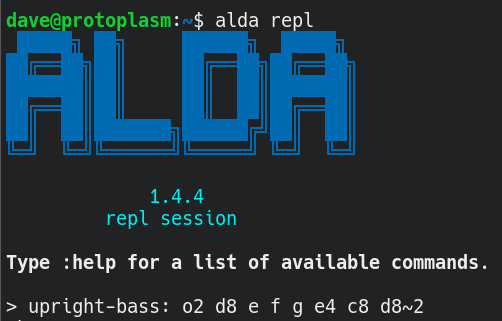

I’m sure that by now, you’re curious what an Alda score looks like. Here is a small example:

piano:

o3

g8 a b > c d e f+ g | a b > c d e f+ g4

g8 f+ e d c < b a g | f+ e d c < b a g4

<< g1/>g/>g/b/>d/gTry it!

It’s easy to get started with Alda. Just follow these instructions to install the latest version.

After you’ve done that, you can check out the short tutorial on the Alda website. It will walk you through the features of the Alda language, one small step at a time.

If you have any questions or thoughts about Alda, feel free to drop into our Slack group anytime and say hello!