This is the third installment in a series where I guide you through learning how to write music using Alda. So far, we’ve covered:

#1: Setup and first notes

#2: Rhythm and meter

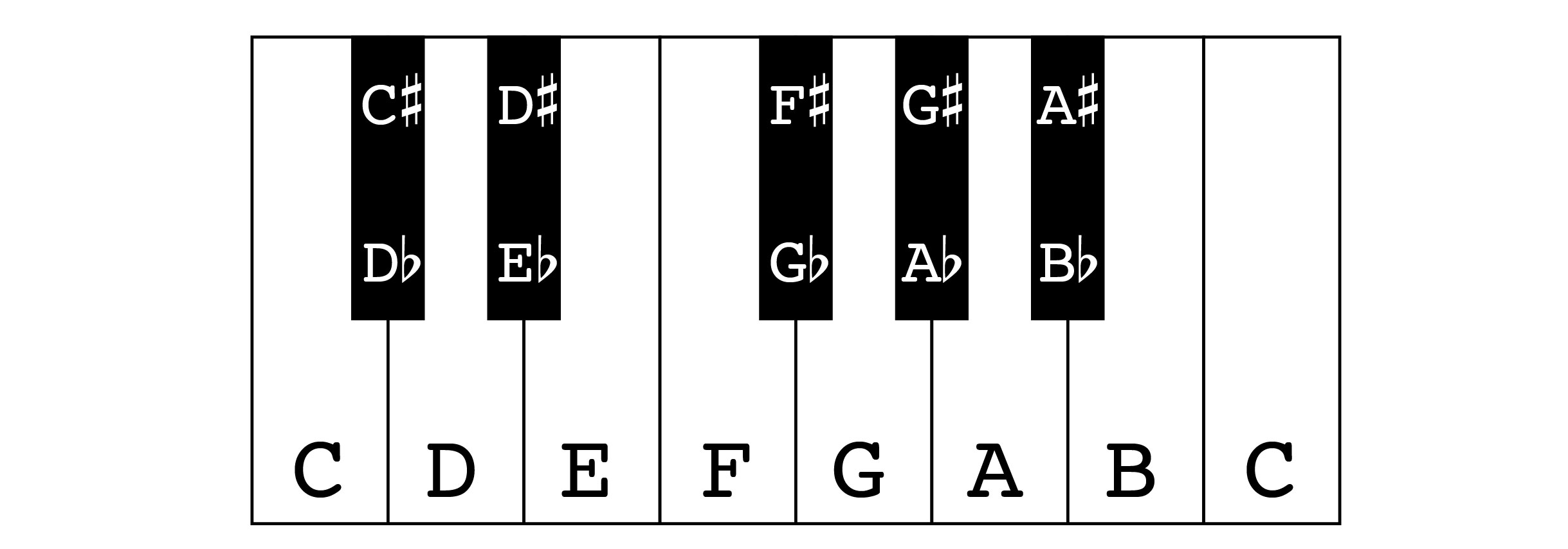

White keys and black keys

So far in this series, we’ve been working with 7 notes:

C D E F G A B C

On a piano keyboard, these are the white keys.

You may have noticed that there are also black keys:

These black keys are the notes in between the white keys. If you look closely, you’ll notice that some of the white keys are right next to each other. These are the notes B and C, and E and F.

With the exception of those notes, every other pair of white keys has a black key in between them:

The distance from each note to the next note – the white or black key immediately to the right on the keyboard – is called a semitone or a half-step. So, a whole step equals two semitones.

Flats and sharps

The black keys in the diagram above are each labeled with two correct names for the note that you hear when you play that key. For example, the black key between C and D is labeled C# (C-sharp) and Db (D-flat).

A sharp increases the pitch of a note by one semitone.

A flat decreases the pitch of a note by one semitone.

So, C# is one semitone higher than C. And Db is one semitone lower than D. They sound exactly the same:

piano: c+ d-You might be tempted to say that C# and Db are “the same note.” This is not exactly true; there are situations where it is considered more correct to use one vs. the other. A more correct (and fancier) statement is that C# and Db are two different enharmonic spellings of the same pitch.

The chromatic scale

The chromatic scale is a scale that includes every one of the 12 notes that make up an octave. To play the scale, you start on a note (any note) and keep going up in semitones until you reach that same note in the next octave up.

Typically, when you’re moving upward, you spell the notes using sharps instead of flats, and when you’re moving downward, you spell the notes using flats.

To illustrate this, here is a chromatic scale going up and then down:

piano:

o4

c8 c+ d d+ e f f+ g g+ a a+ b >

c < b b- a a- g g- f e e- d d- c2Notice two things here:

-

We use sharps on the way up (C, C#, D, D#, …) and flats on the way down (B, Bb, A, Ab, …).

-

There is no flat or sharp note in between E and F, or in between B and C. Remember that when you look on a keyboard, these white keys are right next to each other, with no black keys in between them.

You might now be tempted to think that “there is no such thing as B#, E#, Cb or Fb.” We rarely see these notes, but they do, in fact, exist! They are just different enharmonic spellings of C, F, B, and E, respectively.

piano:

o4

b+ c

e+ f

c- b

f- eSo, why would you write B# when you could write C instead? For you to fully understand this, I would need to go into a deeper explanation than I have space for in this post. I promise that I’ll get to it in a future post, but for now, just keep in mind that B#, E#, Cb and Fb are all real notes, you just aren’t likely to spell them that way, most of the time.

Key signatures

Now that we know how to write all of the notes (not just the white keys), we can write music in different keys other than C major / A minor.

In Writing music with Alda #1, I alluded to the fact that the C major and A minor scales are played by only using the white key notes:

piano:

# C major

o4 c8 d e f g a b > c2

# A minor

o3 a8 b > c d e f g a2These two scales have the same key signature. A key signature is a collection of sharps and flats that always need to be added to certain notes, in order for you to be playing in that key.

C major and A minor have an “empty” key signature, meaning that none of the notes should have any sharps or flats.

Now, let’s learn about a couple more keys.

In the key of D major, the key signature has 2 sharps. When you tell a classically trained musician that a key signature has “2 sharps,” they will probably know exactly which two notes should have a sharp: F and C.

Here is a D major scale. Note that instead of F and C, we have F# and C#:

piano:

o4 d8 e f+ g a b > c+ d2As another example, here is an F major scale. The key signature for F major has 1 flat, so every B becomes Bb:

piano:

o3 f8 g a b- > c d e f2key-signature

But let’s say that you’re not a classically trained musician. How are you supposed to know which notes are flat and sharp in order for the music that you’re writing to be in a particular key?

Alda has you covered.

There is a key-signature (or key-sig, for short) attribute that you can use

that will automatically make all of the right notes flat or sharp for you.

Any attribute in Alda can be made “global” (i.e. affecting all instruments, not just the current one) by adding a

!onto the end. This is an especially good thing to do for attributes liketempoandkey-sigthat are usually shared between all of the instruments in the score. If a piece of music is in Db major, then you’ll probably want all of the instruments to adopt that key signature.This is why, in the example below, we are using

key-sig!instead ofkey-sig.

Notice how these two examples sound different:

piano:

(key-sig! '(c major))

o4 e8 f g a b > c d eAnd:

piano:

(key-sig! '(e flat major))

o4 e8 f g a b > c d eIn both examples, we’ve written the notes out the same way, but in the second example, we’ve set the key signature to Eb major, which automatically turns all of the B’s, E’s, and A’s into Bb’s, Eb’s, and Ab’s.

Exercises

-

Play every “black key” note, spelling each note with a flat.

-

Play every “black key” note, spelling each note with a sharp.

-

Play a chromatic scale, starting on an F in whatever octave you want, going up to the F in the next octave up, then coming back down to F.

-

Play an E major scale. The key signature of E major has 4 sharps: F, C, G, and D. Do not use the

key-signatureattribute. -

Play an E major scale again, but this time, don’t write any of the sharps by hand. Use

key-signatureto set the key signature to E major.

Comments?

Reply to this tweet with any comments, questions, etc.!